Introduction

With the advent of planes in the late 19th century, it would only be a matter of time until these vehicles became new characters in the theatre of war. Fighter aircraft came into being in World War I as an attempt to stop enemy aircraft and dirigibles from gathering information by reconnaissance.

We’ll be exploring two of the wars’ most famous ace fighters: the Red Baron and Douglas Bader.

Red Baron

If it’s an article about ace pilots then it has to feature the infamous Red Baron. A name synonymous with aerial dominance, the Red Baron has become an almost mythical character in the history of the First World War, not just for Germany but the world.

Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen was born on May 2, 1892 and was originally a cavalryman who transferred to the Air Service in 1915. He served as a Reconnaissance officer on both the Eastern and Western Fronts, involved in combat in Russia, France and Belgium.

Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. C. J. von Dühren [Public domain]

However, when trench warfare made traditional cavalry operations obsolete, Richthofen became bored. After taking an interest in German airplanes, he decided to transfer to Die Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches (Imperial German Army Air Service).

While in the Air Service, Manfred (not yet a legend) met another German ace fighter, Oswald Boelcke. He then began training as a pilot in October. Surprisingly, Richthofen did not appear to be a natural: he crashed during his first flight mission where he was in control. He used this experience to set him on a trajectory to becoming a better pilot.

Some time later, Richthofen took to the skies and piloted his craft through a vicious thunderstorm despite the advice of his more experienced colleagues, an act he later regretted. Despite this, he would hone his skills and soon received another visit from Oswald Boelcke. In search of candidates for a new unit, Boelcke approached Richthofen and drafted him into one of Germany’s first fighter squadrons.

The red Fokker Dr1 of Manfred von Richthofen on the ground. [Public Domain]

In 1916, Richthofen became one of the first members of Jasta 2, one of the best-known German Luftstreitkräfte Squadrons in World War I. His first aerial combat victory while in Jasta 2 was over Cambrai, France, in September. A month later, Boelcke was killed in a mid-air collision with a friendly aircraft.

When Richthofen had his first aerial victory confirmed, he had a jeweler in Berlin make a silver cup engraved with the date and model of enemy aircraft. He continued this trend until he had amassed 60 cups but was forced to stop when the supply of silver in Germany had dwindled. Rather than have trophies of a lesser quality, Richthofen stopped having the cups produced altogether.

Richthofen’s brother, who was known for utilizing more aggressive and risky tactics, had collected 40 aerial victories. Unlike his brother, Richthofen adhered to his own set of rules, which were known as the “Dicta Boelcke”. These were a set of aerial combat maneuvers formulated by his squadron leader Boelcke.

Manfred von Richthofen with other members of Jasta 11. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-2004-0430-501 / CC-BY-SA

What set Richthofen apart from many of his peers was the more mechanical nature in which he forewent flashy, acrobatic tactics in place of cold efficiency. He would dive from above, using the sun for concealment while he squad mates covered his rear.

In November 1916, he went to head-to-head with his most famous opponent, British ace Major Lanoe Hawker VC. Richthofen flew an Albatros D. II; Hawker piloted a DH.2. The two were embroiled in a long dogfight, and when Hawker attempted to retreat, Richthofen struck the finishing blow.

In his career, Richthofen was credited with 80 aerial combat victories. On April 21, 1918, while over Morlancourt Ridge, near the Somme River, he was fatally wounded. An eyewitness, Sergeant Ted Smout of the Australian Medical Corps, claimed his last word was “kaputt”.

Douglas Bader

Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader was born in February 1910. He was a Royal Air Force (RAF) fighter ace during World War II, credited with 20 aerial victories, four shared victories, six probables, one shared probable and 11 enemy aircraft damaged.

After joining the RAF in 1928, Bader was commissioned in 1930. An avid sportsman, he also enjoyed motorcycling and would race with other cadets in dangerous activities like speeding, pillion racing and buying and racing motorcars. These were all considered illegal in his service, and Bader was nearly expelled after being caught one too many times.

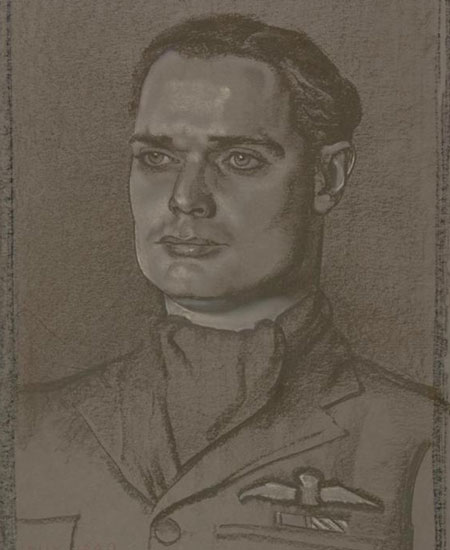

A head and shoulders portrait of Bader in RAF uniform and a cravat. By Eric Kennington [Public domain]

A natural daredevil and quick learner, Bader managed to qualify for solo flight after only 11 hours and fifteen minutes of flight time. He competed with his rival Patrick Coote for the “Sword of Honour” award. This award was a real blade given to the best cadet of the group. Bader lost out to Coote. The latter would go on to achieve 29 aerial victories for the Luftwaffe ace Unteroffizier.

A short time later, Bader became a pilot officer in № 23 Squadron RAF based at Kenley, Surrey. Here, he pushed himself even further, flying illegal and dangerous stunts. His superiors forbid such hazardous maneuvers but Bader ignored them. When he later achieved a less than desirable hit rate along a training course, as well as being taunted by a rival squadron, Bader took to the air to reclaim some of his honor. While his daring stunts had worked this time, he wouldn’t be so lucky in the future.

In training for the Hendon Air Show in 1931, he attempted a series of low-lying acrobatics. The tail of his plane caught the ground, causing him to crash. Bader was rushed off to hospital and had both of his legs amputated. After the incident, his diary read: “Crashed slow-rolling near ground. Bad show.”

Douglas Bader, Fl.Lt. Harry Day and Fl.Off. Geoffrey Stephenson. Training for the 1932 Hendon Air Show. By RAF Museum

Beaten but no broken, Bader fought to regain his abilities. By 1932, and with the help of a pair of artificial legs, he was able to drive a specially modified car, play golf, and dance. Later, he was given another chance to fly. Air Under-Secretary Philip Sassoon allowed him back into the cockpit of an Avro 504, which he was able to pilot.

At the beginning of World War II, Bader returned to the RAF. He was victorious over Dunkirk during the Battle of France in 1940. Then, he was involved in the Battle of Britain, becoming a supporter of Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory and his “Big Wing” experiments.

Squadron Leader Douglas Bader, CO of No. 242 Squadron, seated on his Hawker Hurricane at Duxford, September 1940. By Devon S A (F/O), Royal Air Force official photographer [Public domain]

However, his war was far from over. In August 1941, Bader bailed out over German-occupied France and was captured. He became friends with Adolf Galland, another prominent German fighter ace. During his capture, Bader made several escape attempts, eventually finding himself at the infamous prisoner of war camp at Colditz Castle. In April 1945, he was freed when the camp was liberated by the First United States Army.

Bader continued to fly until ill health stopped him in 1979, at the age of 69.