Sergey Kuksov, Senior Level Artist at Wargaming

Blueprint

The long and difficult process of creating a map begins with the game designer. The Strike Team develop a blueprint, prepare schemes and hand it over for testing. Upon receiving and analyzing stats they place islands, warship spawns and bases across what is to become a new location.

The amended blueprint is then passed over to the designers. Their job is to make each map a unique experience with an original, rich, gaming environment—not your regular seascape with sparse island and lots of water.

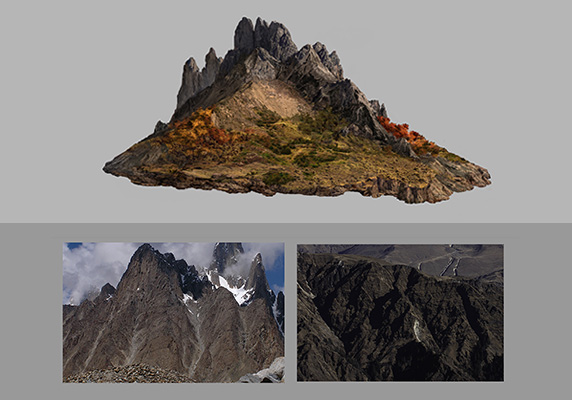

At this point we need to define the environment’s location and setting. Is it a northern or a southern one? Which continent is it? The Art Directors who decide what these places will look like work meticulously to create a really compelling battle experience.

After the setting, color palette and other details have been defined, artists get down to creating sketches of construction objects that will be used to form the islands. They use photos of real locations as a reference. Sometimes artists will invent parts of a landscape, which turn out even more impressive than their real life counterparts. For example, there are no sand dunes on small islands. However, it’s okay to bend reality a little, because they are easily recognizable and a visual indicator of where the player is in the world.

Detalization

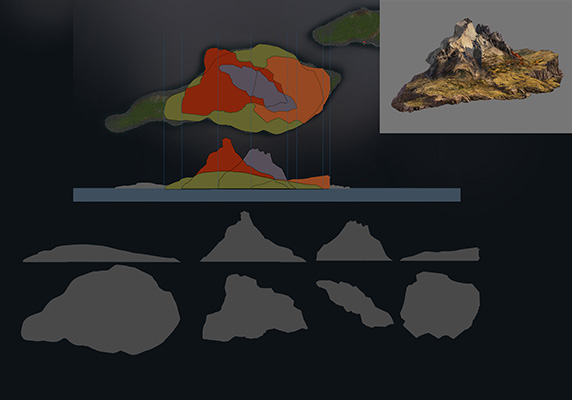

Sketches are handed over to the Level Art Team and production of a new map begins. First off, an artist creates a high poly model in a sculpting editor. These models contain minute details, from grains of sand, small hills, blades of grass, and more. The sheer number of polygons on these models runs into the dozens of millions. Obviously, a model with this much detail can’t make its way into the game, unless one wants to burn a CPU.

So, what’s the point in creating them? Doing this allows the Art Team to retroactively create a low poly model with high poly detalization. After creating a high poly model, the Team create a copy of that, which is far less dense—around 2,500 polygons. While it’s not very detailed—merely a rough copy—it renders all unique features of the original as well as conveying all of its details. The copy is applied to a low poly model to create an object that is low poly yet retains high poly detalization.

Collisions and Trees

Next up is texturing, using the Photoshop Quixel DDO plugin. A lot of it is done manually, only few steps are procedural. A unique smart material (adapting color), tailored for a certain location, is created and then applied for each map to ensure color coherency for all constructor objects. The other specifics of each mesh are handled manually.

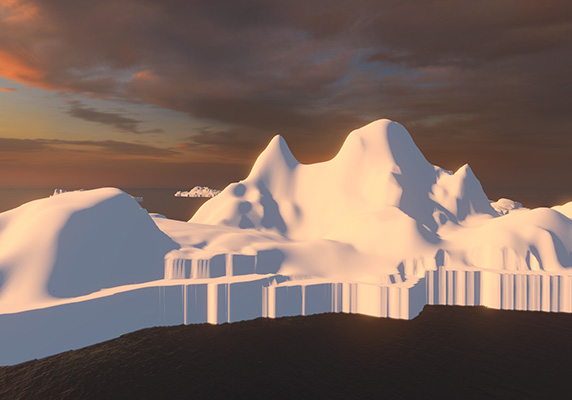

Objects require collision, or better, two of them. Usually, we create a collision that shows how a shell hits an object. It should be consistent with the mesh, with an upper limit of no more than 500 polygons. It’s not much, yet that’s what we aim for. Otherwise, the server side of the game client won’t be able to calculate shots that hit in the environment.

After the collision, the object is exported into the World Editor. There is a total of 7 objects for the future map: some for the coastline, some for the center of the map, others for hilltops and high-altitude areas. This seven-piece set provides a diverse location that reproduces a realistic landscape all the way from mountain peaks to the beach.

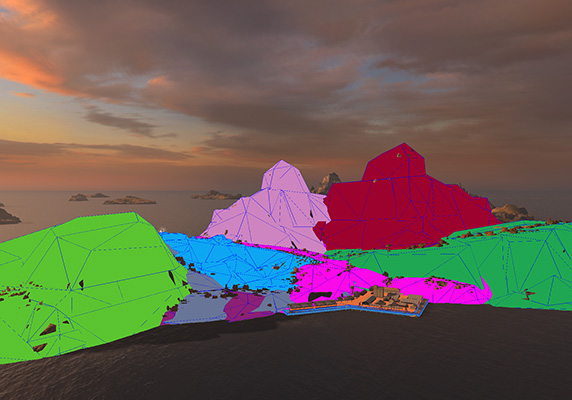

Islands are constructed with extra care and precision: the game designer has to spend a few hours calculating their position, sizes, height and other parameters. Our task is to build them from objects without disturbing the game design behind them.

Once islands are set up, my favorite part begins: we get down to embellishing them. For example, we apply decals to hide junction points between textures and/or liven up the scenery with a meadow or a sandy lot. Then it’s time to “plant” some trees and bushes. The client side has its restrictions. That’s why we can’t place more than four items on a map. Each 3D tree/bush is 750 polygons tops.

There are no LODs (levels of model detail) for trees, and at far distance a 3D model turns into an impostor—a fake 2D sprite object, which replaces a real 3D object. This allows the game to run on older PCs without overloading the CPU when there are a few thousands trees on a close-up. Along with floral objects, maps are decorated with towns, villages and industrial areas.

The work is far from over when there’s a map full of greenery. Next we do the second collision. Its boundaries should repeat the island perimeter and its overwater part. This collision is used for aircraft carriers to ensure they repeat the landscape, as well as warships that interact with the coastline.

Final Touches

The newly finished map goes through a thorough check-up. By going down a special check list, point after point, level artists double-check that everything aligns with the initial design: i.e., all textures are of required size, shaders are where they need to be, content is named correctly, etc. Bugs have a habit of turning up where you never expect them to, you know. It’s our job to fix them before anyone else so they can play on a map that is 100% ready for battle.

After a check-up, it all goes back to where it started: the Game Design Team. The strike team check if the art fits with the gameplay (in other words, that the visuals do not disturb the gameplay): test respawns and bases to ensure everything is in its designated place and, for instance, a ship does not appear partially in the water and partially on land.

The Game Design Team hands the project over to QA. During the automated quality assurance tests, islands get bombarded with shells to find collision errors. AI units cover thousands miles in search of places where a warship broadside clings to objects. Load tests run the newly created maps again and again, measuring the workload of the hardware. The AI camera jumps from the ground up into the skies, measuring the draw time, etc.

QA specialists also check the map for bugs. They often come across trees or other environments hanging in the air. When working on the “North” map, for instance, a spruce hanging in the air went completely unnoticed through internal testing and into the super test. Obviously, players noticed it. Moreover, they pretty much enjoyed the view and even created a separate forum thread “The Flying Spruce Cafe”.

QA is the final stage. Right after it, the new map gets added into the game, then everything is complete and ready for intense naval combat.

For more insights on World of Warships, visit the official portal:

- http://worldofwarships.eu (Europe)

- http://worldofwarships.com (North America)

- http://worldofwarships.asia (Asia)