Overview

The Kempeitai, translated as Military Police Corps, served as the military police of the Japanese Army from 1881 –1945. It draws parallels with Nazi Germany’s Gestapo, in that it was a secret police force rather than overt operation. The Kempeitai was not restricted to the army, but also worked for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). However, the IJN had its own, similar force: the Tokkeitai (contraction of Tokubetsu Keisatsutai), "Special Police Corps"; the Naval Secret Police. Those who were part of the Kempeitai were caked a “kempei”, meaning “military police”.

The Kempeitai formed in 1881 under the decree “Kempei Ordinance”, which was modelled on the Gendarmerie of France. Their code of conduct was known as the “Kempei Rei” in 1898—“rei” roughly meaning “example”. This code was to be amended 26 times by Japan’s defeat in 1945.

A Kempeitai Sōchō uniform at the Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence. By Ahoiyin

349 men made up the initial force, and they enforced the new conscription legislation—bringing in men from peasant families who had resisted the call to arms. In 1907, the Kempeitai was ordered to Korea, with their purview being preserving the peace of the Japanese Army. They still, however, operated in Japan. At this time, the “Tokko” (civilian secret police) was also functioning, of which the Kempeitai had a branch within their organization.

Personnel dressed in the standard M1938 field uniform, typically olive-colored, or wore a cavalry uniform with high black leather boots. While civilian clothes were authorized, a person was required to wear a badge of rank or Japanese Imperial chrysanthemum underneath the jacket lapel. Those in uniform also wore a black chevron on their uniforms and a white armband on the left arm with the characters “ken” (law) and “hei” (soldier). Officers were typically armed with both a cavalry sabre and pistol; enlisted men had a pistol and bayonet; Junior NCOs carried a “shinai” (bamboo kendo sword).

Overseas Operations

United States and Mexico

Naturally, a secret operation had to use cover locations to hide their presence and subsequent activities. In Tijuana, Mexico, this took the form of the Molino Rojo (Red Mill), which was a brothel and was used as a meeting place. This HQ was situated in the infamous Zona Norte, a red-light district, the largest in North America. The Molino Rojo was around 15 miles from the U.S. Navy's San Diego Destroyer Base and the North Island Naval Air Station.

While operating in Mexico, an Imperial Navy Lieutenant Commander and subversive agent—a former exchange student at America’s Stanford University—lured an ex-U.S. Navy yeoman, via monthly payments, to be an American spy. The man was hired to obtain intelligence from the crews.

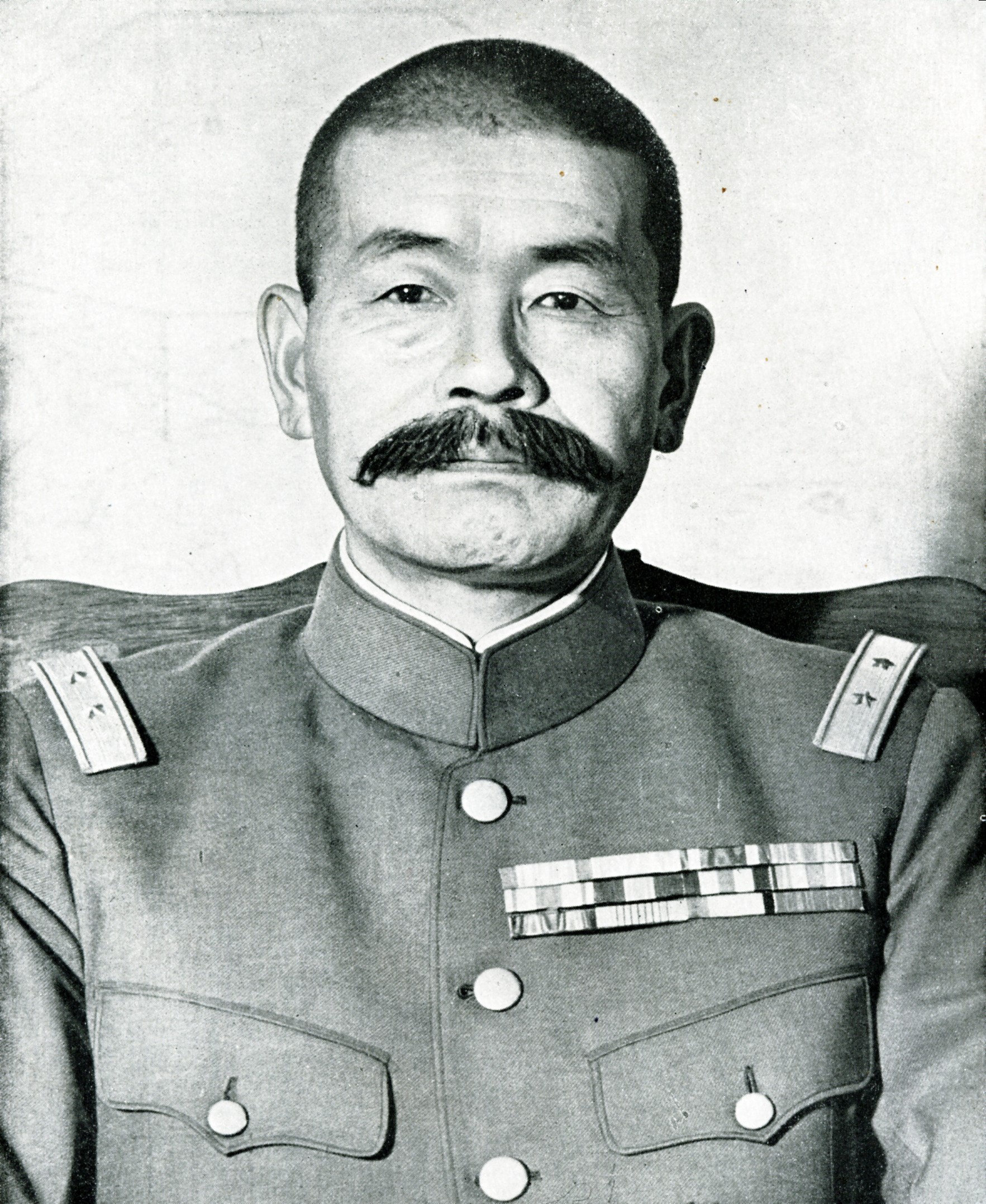

Shizuichi Tanaka, a famous commander of Imperial Japanese Army in days of World War II. The source book, The Philippines Expeditionary Force, names him "Army Commander Tanaka" without further details. CC

Underground Actions

Japan also secretly allied themselves with societies in their country that had ultra-nationalist agendas. These included Genyosha (Dark Ocean Society), Kokuryu-kai (Amur River Society or Black Dragon Society), and organized criminal enterprises such as Yakuza crime syndicates.

The Dark Ocean founder Mitsuru Toyama had links to the Kempeitai, and the latter relied on these groups for manpower. The Black Dragons were active along the Pacific Coast of North and South America. Many of its members had a legitimate career in politics and several were members of the Kempeitai.

Europe

Spain was neutral during World War II. Here, spies working under the guise of Japanese ambassadors could control worldwide spy rings and coordinate the exchange of intelligence with other Axis Forces. This was achievable through Germany's Abwehr general staff intelligence agency and Italy's Military Secret Service. Like Spain, Portugal’s neutrality was an integral point of informational exchange. Germany even went so far to allow the Japanese ambassador outrank the Japanese diplomat in Madrid and Lisbon, because the majority of information was funneled through Japan’s Embassy.

The Japanese Ambassador was close friends with the chief of Germany’s secret service. There were also diplomats in Afghanistan that spied on the Soviet Union, Iran and India, which fed information into the Japanese Madrid center. This network even extended to Great Britain and America. Early in the war, the Japanese ambassador in Spain established a spy ring in the U.S., with the help of Spanish operatives.

A victory parade in Shanghai. Credit to Military-history.org

Legacy of the Kempeitai

The brutality of the Kempeitai became notorious in Korea and other occupied territories. This extended to the homeland as well; the Japanese people held no love for the police force, especially because they were used to ensure that the public was loyal to the war.

In total, the United States Army estimated that there were over 36,000 regular members of the Kempeitai by the end of the war. This number was attributed to the fact that Japan’s occupation of a number of overseas territories meant they needed locals to act as part of their force.

During wartime, the Kempeitai had a number of responsibilities including travel permits, labor recruitment, counterintelligence and counter-propaganda. The latter was run by the “Tokko- Kempeitai, classed as “anti-ideological work”. Additionally, the Kempeitai handled Supply requisitioning and rationing, psychological operations and propaganda, and rear area security. Even towards the end World War II, they still arrested people for antiwar sentiment and defeatism.