World War I saw a huge number of female volunteers on all sides. A large number of these women were drafted into the civilian work force to replace men who had been conscripted or to work in munitions factories. However, there were a number of female soldiers who chose to take their fight to the front lines and beyond.

Russia—Maria Bochkareva

Maria Leontievna Bochkareva fought in World War I and formed the Women’s Battalion of Death. Before her military exploits, Bochkareva had suffered a difficult life from her early years to adulthood. After the outbreak of World War I, she returned to Tomsk, where she had lived some time before. Here she joined the 25th Tomsk Reserve Battalion of the Imperial Russian Army by securing the personal permission of Tsar Nicholas II. The men in her regiment would regularly harass Bochkareva until she proved her battle prowess: she was twice wounded and decorated three times for bravery.

When the Tsar abdicated in March 1917, Bochkareva was ordered to create an all-female combat unit by Minister of War Alexander Kerensky. The unit would be the first women’s battalion to be organized in Russia. Many women volunteered for Bochkareva’s 1st Russian Women’s Battalion of Death. In the end, her strict discipline culled the ranks from 2,000 to 300.

Maria Bochkareva. Library of Congress

The unit trained intensely for a month, then sent to the Russian Western Front to participate in the Kerensky Offensive. They were involved in one large-scale battle, close to the town of Smorgon. Though the women fought well, most of the male soldiers had already been demoralized.

Further women’s units were created in Russia during the spring and summer of 1917. The 1st Petrograd Women’s Battalion were used in the defense of the Winter Palace, and, at the time of the October Revolution, Bochkareva and her unit were fighting at the front. However, the latter’s unit disbanded after hostility from their own male troops. Upon her return to Petrograd, she was initially detained by the Bolsheviks, but then released.

Bochkareva had hoped to return to Tomsk, she received a telegram asking her to transport a message to General Lavr Kornilov, who was commanding a White Army in the Caucasus. When she left his headquarters, she was once again detained by the Bolsheviks and scheduled to be executed for her involvement with the Whites. However, Bochkareva was rescued by a soldier who had served with her in the Imperial Army, convincing her captors to stay her execution.

The Winter Palace, an iconic simple of the October Revolution. Photographed by Siyad Ma

Securing a passport, she was able to leave the country to Vladivostok, and then to the United States. In the U.S., she met President Woodrow Wilson, urging him to intervene in Russia. Later, Bochkareva would travel to Great Britain, where she was granted an audience with King George V. The British War Office then gave her funding to return to Russia.

She arrived in Arkhangelsk in August 1918, attempting to organize another unit, but failed. Then, in April 1919, Bochkareva returned to Tomsk in the hopes of forming a women’s medical detachment under the White admiral Aleksandr Kolchak. The Bolsheviks captured her again and sent her to Krasnoyarsk. After four months of interrogation, she was sentenced to be executed as an enemy of the people. The Cheka carried out her execution by firing squad on May 16, 1920.

Great Britain—Dorothy Lawrence

Dorothy Lawrence was an English reporter, who went on to secretly pose as a man to become a soldier during World War I. Her success as a journalist included articles published in The Times, and, after the outbreak of the war, she wrote a number of articles for Fleet Street newspapers.

In 1915, she travelled to France and volunteered as a civilian employee of the Voluntary Aid Detachment, though was rejected. Not content with being rebuffed, Lawrence entered the war zone via the French sector as a freelance war correspondent. However, she was arrested by the French police just short of the front line and ordered to leave.

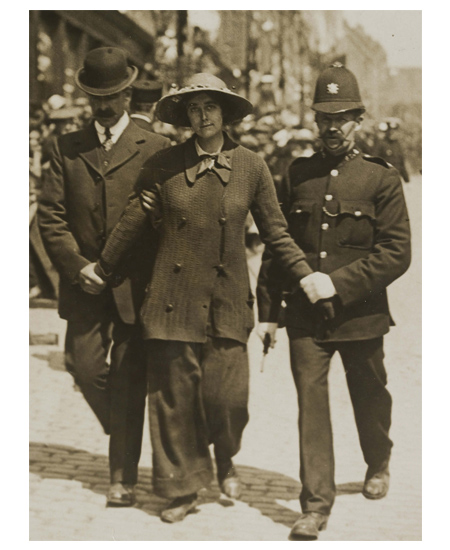

Lawrence being arrested by police officers. Museum of London

Upon her return to Paris, she decided that the only way to get her story was to pose as a man, saying: “I’ll see what an ordinary English girl, without credentials or money can accomplish.” Lawrence befriended two British Army soldiers, persuaded them to smuggle her, little by little, when the men had their uniform washed. For her hair, she persuaded two Scottish military policemen to cut her hair to the military style, darkened her complexion with disinfectant, and tanned herself with shoe polish. To learn the proper etiquette, she asked her soldier friends to teach her how to drill and march. Finally, to reach the frontlines, Lawrence obtained forged identity papers of an officer.

Instead of taking an army convoy to reach the British sector of the Somme, she set out by bicycle. Along the way, Lawrence met Tom Dunn, a member of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). He offered to assist in her ploy, finding Lawrence an abandoned cottage where she could stay at night upon returning from the front line.

On the front line, Lawrence worked as a sapper with the 179 Tunneling Company, who was a specialist mine-laying company that operated within 400 years of the front line. Here, she helped to dig tunnels and worked with the trenches. This work took its toll. She suffered constant chills, rheumatism, and fainting fits. Ten days of service later, she informed her commanding sergeant, who put her under military arrest.

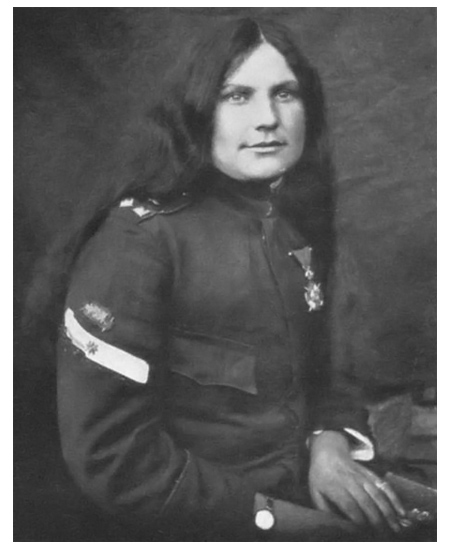

Lawrence as a soldier and civilian

When Lawrence was taken back to the BEF headquarters, they believed her to be a spy, then declared a prisoner of war. A short time later, she was taken to Third Army headquarters in Calais, where she was interrogated by six generals and approximately twenty other officers. From here, she went to Saint-Omer for further interrogation. By this time, the army was concerned that word would get out that a woman had managed to infiltrate their ranks.

Lawrence remained in France until after the Battle of Loos. She was later sent back to London. Here she attempted to write about her experiences but was stopped by the War Office. In 1919, she finally wrote her book: Sapper Dorothy Lawrence: The Only English Woman Soldier, though it was still heavily censored by the War Office.

Serbia—Milunka Savić

Milunka Savić fought in the Balkan Wars and in World War I. She has been recognized as the most-decorated female combatant in the history of warfare, and was wounded no fewer than nine times during her service.

Savić was born in the village of Koprivnica, Serbia. When her brother received his call-up papers for mobilization for the Second Balkan War, in 1913, she chose to go in his place. She cut her hair, donned men’s clothing and joined the Serbian Army.

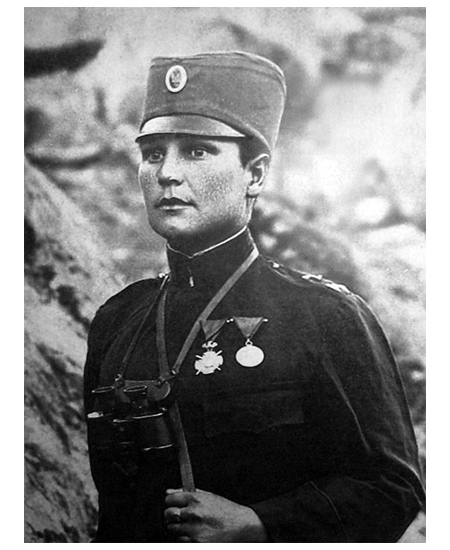

Milunka Savitch, 1914-1918. imus.org

She found herself quickly in battle, receiving her first medal and promotion to corporal in the Battle of Bregalnica. Only when she was injured in battle and recovering in hospital was her gender truly revealed, much to her physicians’ surprise.

The Serbian then found themselves in a predicament. On the one hand, they did not want to punish her, on the other hand, they did not deem it suitable for young women to be in combat. They offered her a transfer to the medical division, but she refused. Savić wanted to fight for her country as a combatant. After thinking for it for around an hour, her commanding office agreed to send her back into the infantry.

Milunka Savitch with medal. srpskidespot.org.yu

In 1914, while World War I was still in its infancy, Savić was ordered her first Karađorđe Star with Swords after the Battle of Kolubara. She then received her second Karađorđe Star (featuring Swords) after the Battle of the Crna Bend in 1916: Savić had single-handedly captured 23 Bulgarian soldiers.

Her other military honors include the French Légion d’Honneur (Legion of Honour) twice, Russian Cross of St. George, British medal of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael, Serbian Miloš Obilić medal. She was also the only female recipient of the French Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 with the gold palm attribute for service in World War I.