Introduction

Propaganda is the art of influence that seeks to manipulate an attitude of a group of people toward a cause or political position. By its nature, it not impartial and is usually biased. It is often selective with the facts or truths it presents, and will often appeal to fears or concerns of the group it is targeting. Over time, propaganda has acquired strongly negative connotations and can seem quite outdated by today’s standards. However, during both World Wars I and II, propaganda posters caught the eye and influenced the populace, with their striking artistic style still rippling through art to this day. We have taken a look at some prominent and interesting examples from both sides.

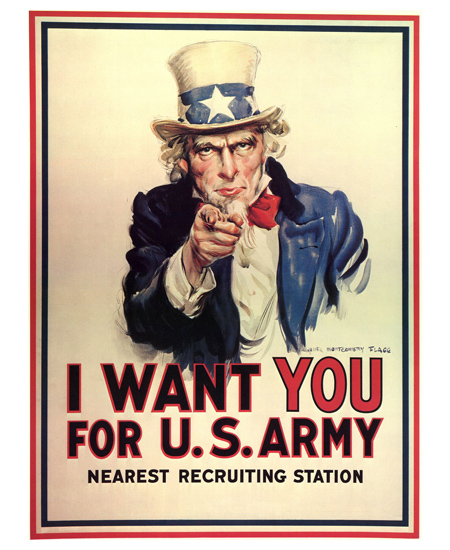

Uncle Sam (U.S.A)

“I Want You for U.S. Army”

The image of Uncle Sam (often viewed as the personification of the United States) from the World War I recruitment poster has become one of the U.S.A.’s most iconic images. James Montgomery Flagg, a prominent U.S. artist, designed 46 posters for the government, but his most famous was the “I Want You for U.S. Army”. Versions of the poster were then used again for World War II.

During both World Wars, posters were meant to instill people with a positive and patriotic outlook on the conflict. Posters were encouraging not just men to join the army, but every citizen of the United States to contribute to the war effort and do their part, whether at home or abroad. As we can see in the above example, red, white and blue are the colors which dominate the poster.

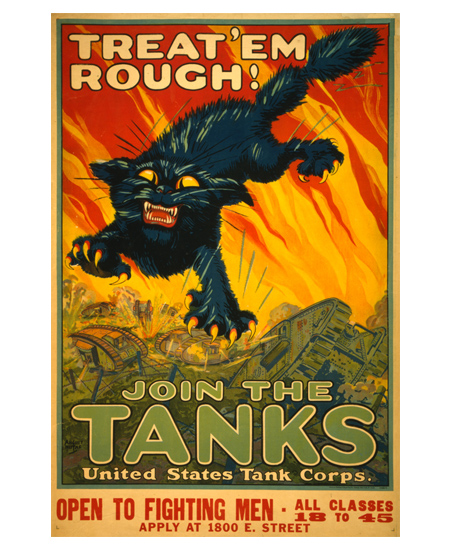

Treat ‘em Rough (U.S.A)

“Treat ‘em Rough” 1917

This poster, by artist August William Hutaf was created for the United States Tank Corps.

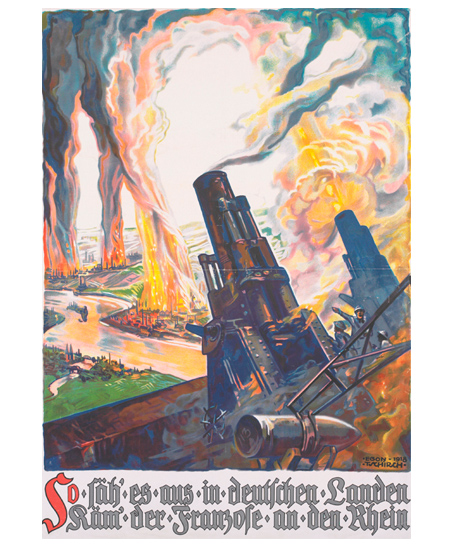

This Is How It Would Look in German Lands (Germany)

“So Säh es aus in Deutschen Landen” 1918

A contrast from the usual stark colors that are in a number of propaganda posters, the artist, Egon Tschirch, worked as a freelance painter in Rostock. His trips around southern France, Africa and Tunisia brought vivid color and luminosity to his work. Tschirch was also a soldier in World War I.

The colors in the poster stuck with red and black, which were used in a great deal of Germany’s propaganda work, as well as the gothic script. In the poster we can see two French howitzers that are firing on a city on the banks of the Rhine, where great plumes of smoke rise from the industrial areas.

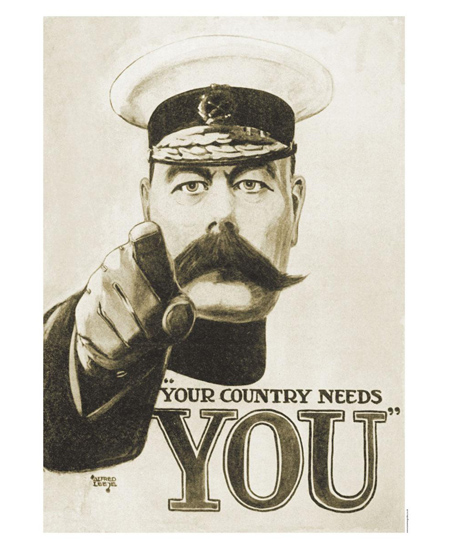

Lord Kitchener (Britain)

“Your Country Needs You” 1914

Perhaps one of the most famous recruitment posters of World War I showing Lord Kitchener. The poster depicts Lord Kitchener, who was the British Secretary of State for War, wearing the cap of a British Field Marshal and calling on the viewer to join the British Army to fight against the Central Powers. The poster would go on to influence the United States and the Soviet Union.

Before the institution of conscription in 1916, the United Kingdom has relied on upon volunteers for the army. However, with the outbreak of World War I, recruiting posters had not really been used since the Napoleonic War. The fact that Kitchener was an actively serving military officer leant credibility to the poster. Le Bas of Caxton Advertising chose Kitchener for the advertisement, saying Kitchener was “the only soldier with a great war name, won in the field, within the memory of the thousands of men the country wanted.”

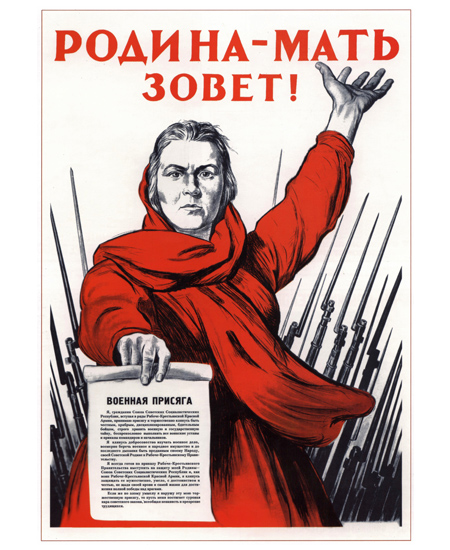

Motherland (Soviet)

“Motherland Calls” 1941

This was, perhaps, the first and most famous Soviet poster of World War II. The image itself depicts “Mother Russia” in red, the color most strongly linked to Soviet Russia. In her hand she is holding a piece of paper which on it is the Red Army oath.

The poster was created in July 1941 by Irakli Toidze, a famous socialist realism artist, during the first days of the Great Patriotic War. Over time, it has become one of the most reconcilable pieces of Soviet art, and stands as a symbol of Russian liberation. The Motherland Calls also influenced Russia’s largest statue, also dubbed “The Motherland Calls” (The Mamayev Monument), which stands in Volgograd (former Stalingrad).

Manchukuo (Japanese)

“With the cooperation of Japan, China, and Manchukuo the world can be in peace” 1935

Japanese propaganda tended to rely on pre-war elements of statism in Shōwa Japan. Later, new forms of propaganda were introduced during World War II to persuade occupied countries of the benefits of Japanese rule. These attempted to undermine American troops’ morale, counteract claims of Japanese atrocities, and make it appear as though the Japanese were victorious.

The poster above is of “Manchuko”; its purpose is to promote harmony between Japanese, Chinese, and Manchu peoples. Its caption reads: “With the help of Japan, China, and Manchukuo, the world can be in peace.” The flags shown are, left to right: the flag of Manchukuo; the flag of Japan; the “Five Races Under One Union” flag.

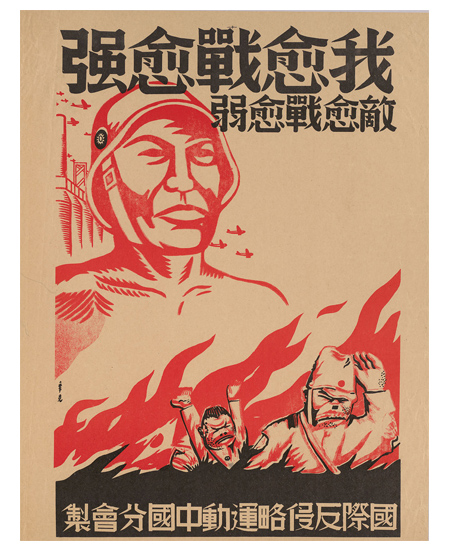

The More We Fight, the Stronger We Are (China)

“The More We Fight the Stronger We Are. The More Enemies [we] Fight the Weaker They Get” 1940

Earlier Chinese propaganda posters are largely associated with the image of Mao Zedong, as well as the rising sun over a sea of red flags. Even before this, during the long march (1934–1935), graphic sheets were produced and distributed to the local people to support and propagate the Communist ideology. They were originally simply designed in black and white, being distributed between the local populace.

The above poster uses red once again, and served to garner support for the Chinese to overthrow the Japanese troops that had occupied their land. After the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, propaganda posters became even more popular method for spreading the message about the Communist party.

Drive Them Out (Italy)

“Cacciali via!”

The Fascist regime used propaganda heavily to influence its citizens. This included pageantry and rhetoric, its purpose being to inspire the nation to unite and obey. In the beginning, propaganda was under the control of the press office, until a Ministry of Popular Culture was created in 1937. Two years before, a special propaganda ministry was created, whose purpose it was to espouse fascism, refute enemy lies, and clear up ambiguity.

By Ugo Finozzi

Posters were a powerful propaganda tool, and many were designed by some of Italy’s leading graphic artists. The above poster shows a mother clinging to her child as a soldier, holding a dagger, rushes forward toward flames with the text “Drive them out!”. It was created by Ugo Finozzi.